Huh? That doesn’t make sense. Depth perception is in the Z (depth) axis. It’s neither in the X (horizontal) or Y (vertical) axis. You get the exact same stereo vision depth perception regardless of the orientation of your eyes.

Imagine a triangle with your eyes and the subject at a distance as the points. This triangle can be rotated around the long axis without changing anything. Tilting your head does nothing for visual depth perception.

For singular dots in space your argument would be valid, but real objects are often more complicated. If the eyes can’t reliably lock onto the same spot along the X-axis due to a repeating pattern or a complete lack of detail along said axis, tilting the head shifts the whole situation and allows the eyes to zero in on a fixed point to perceive depth. An extreme example: If you look at two horizontal featureless lines (offering no details along their length to lock onto, brushed metal railings for example) positioned one behind the other, running perpendicular to the field of view in the direction of the X-axis. The only way for depth perception to work here is to tilt the head to introduce a difference along the Y-axis.

Repeating patterns with the right spacing (e.g. grids, lattices) in that same plane can also confuse depth perception, in which case the head tilt often helps.

Another (marginal) benefit of head tilting is the fact that as the head rotates, the eyes physically move, possibly revealing additional detail that may have been obstructed from the previous vantage points. All this for a much lower energy expenditure than the whole animal moving itself.

Oh and one thing that popped into mind from personal experience as I am writing this: In darkness tilting the head helps discern between shapes that are just lingering on your retinas after looking at a brighter thing earlier (rotates along with the eyes) vs. dim things that might actually be there right now (stays in the same orientation relative to the surroundings).

Your vision is always a singular dot in space, unless you have amblyopia or something else causing your eyes to point in different directions. Even if you’re looking at a featureless line, your eyes are fixed on a single point in space. It’s not like one eye is looking somewhere different from the other eye. The triangle still exists.

There is no difference to stereo vision depth perception regardless of how the view points are oriented in the X and Y axis. The practical proof for this is in rangefinders; neither simple consumer stereo rangefinders nor complicated military stereo rangefinders, such as those found on battleships

or antiaircraft guns, are oriented in the Y axis to gain some advantage. There’s no need. The triangle is the same regardless of X-Y orientation.

I see what you’re saying about the example of two completely featureless lines oriented exactly along the X axis in a completely featureless space, as this wouldn’t work with a coincidence rangefinder, but this is an edge case and not something you’d encounter in real life. You’d also have other cues for depth perception beyond just stereopsis.

I do not know exactly why or how, but tilting my head in different directions really helps me see, hear, and asses things & situations much better.

Overtime, I noticed that my brain sometimes ignores certain things by default, but tilting my head around resets my brain into noticing them.

For example, my brain often ignores bikes, motorcycles, and pedestrians on the side walk because my brain is always hyper focused on not crashing into the car in front of me or behind me-- but driving with my head cocked in different angles prevents my brain from ignoring them.

I have yet to cause an auto accident in over 20 years of driving because I drive with my head on a swivel like I got a fucking lidar system or something I gotta point in all directions.

I also can hear different pitches and background instruments in music a lot better if I’m swiveling my head around in different angles or if I close my eyes.

When we go to classical music concerts, my boyfriend often tells me I look like those artic foxes hunting for mice under the snow-- like I’m trying to triangulate whatever I’m hearing.

I cannot tell you how or why it works, only that it does for me.

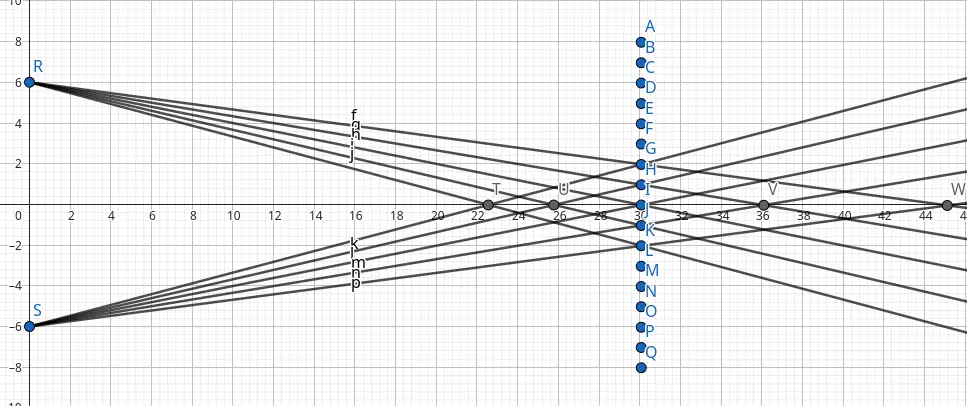

It’s not that the triangle doesn’t exist, but that the brain has multiple options for forming said triangle, only one of which results in the real image. Threw the following together to illustrate:

I was looking at a grid lattice wall paneling just this week which had the same effect.

If the pattern is perfectly uniform, the eyes can’t distinguish between different features in it. The whole situation is a bit comparable to a stereoscope. Shifting the eyes out of plane with the pattern causes the false images to split vertically while the one true image remains. This isn’t an issue most of the time, but it does demonstrate how some situations invalid for stareopsis can be tackled with a simple head tilt.

Rangefinders aren’t usually looking at patterns in walls for example. Aircraft or ships don’t create uniform enough patterns. Yes it’s still an edge case, but I just wanted to explain my point that tilting the head does offer the brain more to work with, which in some confusing situations can be critical to correctly perceiving the situation.

Huh? That doesn’t make sense. Depth perception is in the Z (depth) axis. It’s neither in the X (horizontal) or Y (vertical) axis. You get the exact same stereo vision depth perception regardless of the orientation of your eyes.

Imagine a triangle with your eyes and the subject at a distance as the points. This triangle can be rotated around the long axis without changing anything. Tilting your head does nothing for visual depth perception.

For singular dots in space your argument would be valid, but real objects are often more complicated. If the eyes can’t reliably lock onto the same spot along the X-axis due to a repeating pattern or a complete lack of detail along said axis, tilting the head shifts the whole situation and allows the eyes to zero in on a fixed point to perceive depth. An extreme example: If you look at two horizontal featureless lines (offering no details along their length to lock onto, brushed metal railings for example) positioned one behind the other, running perpendicular to the field of view in the direction of the X-axis. The only way for depth perception to work here is to tilt the head to introduce a difference along the Y-axis. Repeating patterns with the right spacing (e.g. grids, lattices) in that same plane can also confuse depth perception, in which case the head tilt often helps.

Another (marginal) benefit of head tilting is the fact that as the head rotates, the eyes physically move, possibly revealing additional detail that may have been obstructed from the previous vantage points. All this for a much lower energy expenditure than the whole animal moving itself.

Oh and one thing that popped into mind from personal experience as I am writing this: In darkness tilting the head helps discern between shapes that are just lingering on your retinas after looking at a brighter thing earlier (rotates along with the eyes) vs. dim things that might actually be there right now (stays in the same orientation relative to the surroundings).

Your vision is always a singular dot in space, unless you have amblyopia or something else causing your eyes to point in different directions. Even if you’re looking at a featureless line, your eyes are fixed on a single point in space. It’s not like one eye is looking somewhere different from the other eye. The triangle still exists.

There is no difference to stereo vision depth perception regardless of how the view points are oriented in the X and Y axis. The practical proof for this is in rangefinders; neither simple consumer stereo rangefinders nor complicated military stereo rangefinders, such as those found on battleships or antiaircraft guns, are oriented in the Y axis to gain some advantage. There’s no need. The triangle is the same regardless of X-Y orientation.

I see what you’re saying about the example of two completely featureless lines oriented exactly along the X axis in a completely featureless space, as this wouldn’t work with a coincidence rangefinder, but this is an edge case and not something you’d encounter in real life. You’d also have other cues for depth perception beyond just stereopsis.

I do not know exactly why or how, but tilting my head in different directions really helps me see, hear, and asses things & situations much better.

Overtime, I noticed that my brain sometimes ignores certain things by default, but tilting my head around resets my brain into noticing them.

For example, my brain often ignores bikes, motorcycles, and pedestrians on the side walk because my brain is always hyper focused on not crashing into the car in front of me or behind me-- but driving with my head cocked in different angles prevents my brain from ignoring them.

I have yet to cause an auto accident in over 20 years of driving because I drive with my head on a swivel like I got a fucking lidar system or something I gotta point in all directions.

I also can hear different pitches and background instruments in music a lot better if I’m swiveling my head around in different angles or if I close my eyes.

When we go to classical music concerts, my boyfriend often tells me I look like those artic foxes hunting for mice under the snow-- like I’m trying to triangulate whatever I’m hearing.

I cannot tell you how or why it works, only that it does for me.

It’s not that the triangle doesn’t exist, but that the brain has multiple options for forming said triangle, only one of which results in the real image. Threw the following together to illustrate:

I was looking at a grid lattice wall paneling just this week which had the same effect. If the pattern is perfectly uniform, the eyes can’t distinguish between different features in it. The whole situation is a bit comparable to a stereoscope. Shifting the eyes out of plane with the pattern causes the false images to split vertically while the one true image remains. This isn’t an issue most of the time, but it does demonstrate how some situations invalid for stareopsis can be tackled with a simple head tilt.

Rangefinders aren’t usually looking at patterns in walls for example. Aircraft or ships don’t create uniform enough patterns. Yes it’s still an edge case, but I just wanted to explain my point that tilting the head does offer the brain more to work with, which in some confusing situations can be critical to correctly perceiving the situation.

Why you looking at me like that?

-I’m expanding you into the third dimension!

Oh, cool?